ABOUT MARIA MITCHELL

For Students & Teachers

America’s First Woman Astronomer

Maria Mitchell was one of the most famous figures in Nantucket history, and was a force behind women’s rights and women’s education of the nineteenth century.

It would be impossible to describe her contributions in just a few short sentences: Like many island women, she fulfilled many roles during her lifetime, both on Nantucket and “off-island.” However, she is most known as the first professional American woman astronomer, a title she received when she discovered a telescopic comet from the roof of the Pacific National Bank on Main Street. Although she would work tirelessly as an astronomer and teacher for the rest of her life, Maria Mitchell was also a librarian, a student of languages, a world traveler, and a supporter of universal rights for women.

Read on below to learn more about the incredible life and legacy of the much beloved “Miss Mitchell."

“The world of learning is so broad, and the human soul is so limited in power! We reach forth and strain every nerve, but we seize only a bit of the curtain that hides the infinite from us.”

– Maria Mitchell

Lesson Plans

- The Past and Present of Women in Science

An Examination of Women in Science from the nineteenth Century to the twenty-first

Grades: 8-9 (potentially for high honors grade 7) - Women's Rights Lesson Plan

- Additional Resource for Lesson: The Need of Women in Science

- Mapping Lesson Plan

Mapping of Maria Mitchell’s Journeys

Grades: 6-7 - Mapping Lesson Plan

- Additional Resource for Lesson: Maria Mitchell Journal Entries

- Exploring the Skies with the Mitchell Sisters

Learning about Solar and Lunar eclipses and the lives of Maria and Phebe Mitchell!

Grades: 1-3 - Eclipse Lesson Plan

- Additional Resources for Lesson: Maria Mitchell Journals & Eclipse Images

Created by Megan (Meg) Bellavance, Mitchell House Curatorial Intern, Summer 2019

- Early Childhood

Maria Mitchell was born on Nantucket at 1 Vestal Street on August 1, 1818, shortly after her parents, William and Lydia Coleman Mitchell, purchased the home. Maria was their third child, following two elder children, a boy named Andrew and a girl named Sally. During their time there, Maria’s mother would give birth to seven other children. Like many 19th century Nantucket households, Maria’s family belonged to the Religious Society of Friends, or “Quaker Meeting.” On Nantucket many people became Quakers because it allowed them more freedom in personal and business dealings. Lydia Coleman Mitchell’s ancestors had been among the first settlers to flee Puritan rule in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and settle on Nantucket; William Mitchell’s family followed just a few years later.

- Life in the Mitchell Home

Growing up in a Quaker household meant a simple life. Although the Mitchells certainly stressed these values, William Mitchell was known for making attempts to liven up daily life. Quakers were not allowed to dress in or display bright colors, but Mr. Mitchell found opportunities to get around the rules. According to Phebe, one of Maria’s sisters, “If he were buying books, and there was a variety of binding, he always chose the copies with red covers. Even the wooden framework of the reflecting telescope which he used was painted a brilliant red.” The sitting room was decorated with floral wallpaper featuring pink roses. From the ceiling, William Mitchell hung “a glass ball, filled with water, [which he used] in his experiments on the polarization of light, flashing its dancing rainbows about the room.”

Maria was fascinated by her father’s investigations. Nantucketers, it seemed, were connected to the study of the skies by nature. The work of astronomers was essential to the safe navigation of the many whaling and merchant ships that sailed from the island during the 1800s. Nantucket was then the whaling capital of the world, and William Mitchell was responsible for ensuring that whaling crews always knew their exact locations in the vast seas. He rated chronometers, ships’ clocks that had been invented less than a hundred years before and that allowed sailors to figure out their longitude.

From the time she was twelve years old, Maria served as an important helper for her father. As the family observed a solar eclipse over the island in 1831, Maria counted the seconds of the eclipse and pinpointed the longitude of their house. Two years later, whaling captains entrusted the fourteen-year-old Maria to rate their chronometers on her own. William Mitchell built a small study on the landing of an old staircase for his children, but it was most often used by Maria for all of the calculations and work associated with working with her father and on her own.

- Student

Although Maria showed a special ability for calculations and astronomy, all Quaker parents made sure to provide a thorough and equal education to their male and female children.

William Mitchell himself was a school teacher. Maria’s sister, Phebe Mitchell, wrote that education continued even after the children had returned home from a day at school: “the children of a family sat around the table in the evenings and studied their lessons for the next day, the parents or the older children assisting the younger if the lessons were too difficult.” Children in Maria’s day also attended school five days a week, for six hours a day, but were only given four weeks vacation in the summer. For part of their childhoods Maria and her siblings attended the public school where William was schoolmaster.

Later, they attended a private school he founded. After William Mitchell ended his career as a teacher, Maria found important mentors and supporters in several of her other teachers. One sent her a hundred dollars with which to buy books to continue her individual study; another helped her to acquire a telescope. The three most important skills taught in schools were reading, writing, and basic arithmetic. Maria grew up in an environment where home learning through books was also encouraged. Her mother had been a librarian at Siasconset, a community on the island, and Maria studied mathematics and astronomy books throughout her childhood

- Teacher & Librarian

Maria was so inspired by her experiences with education that she became a teacher’s assistant at her former school at the age of sixteen. She founded a private school on Traders’ Lane, near Vestal Street, a year later, but left that post to become the first librarian at Nantucket’s Atheneum in 1836.

The Atheneum was not a public, free library, but Maria’s sister Phebe noted that the price of subscription “was very inexpensive to the shareholders.” Since the library was open during limited hours and was often quiet, Maria spent much of her almost twenty years there continuing her personal education through learning subjects like Latin, German, celestial mechanics (physics), and advanced mathematics. At around the time Maria took up her job as librarian, she and her family moved to the Pacific National Bank, where her father had taken a position as chief cashier.

In Maria’s time, the Atheneum was known for serving as a meeting place for forward thinkers of the time, and as the site of public lectures by important figures, such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Thoreau, native Nantucketer Lucretia Coffin Mott, and Frederick Douglass.

Maria grew comfortable with her role at the Atheneum, chatting with her patrons and monitoring the reading habits of the young children who came to see her at her post. Maria’s quiet life, however, would soon be transformed by a major event.

The Mitchells now lived in the center of town, at the top of lower Main Street, and the Atheneum was just a short walk away. Maria was known for aiding her brothers and sisters. Phebe tells one story about Maria’s helping to pay for a piano that one of her sisters wanted to purchase. However, music was prohibited by Quaker rules. Maria was the one to greet her parents on the stairs with the announcement that they had brought the forbidden piano into the house. Perhaps it is not surprising that both Maria and her siblings would all eventually leave Quaker meeting in order to allow themselves greater personal freedom.

- Comet

Maria climbed the stairs to the roof of the Pacific National Bank each night to “sweep the sky” with the family’s telescope, a brass 2 3/4 inch refractor that they called “the Little Dollond.” On October 1, 1847, Maria is said to have left a family party to “don her regimentals” and observe. While looking over a familiar patch of sky, Maria noticed an object she had never seen before, and went to her father to declare that she may have seen a new comet. A comet is a frozen mass, often made of rock and ice that orbits around the Sun. William Mitchell urged her to make her discovery public, but Maria was reluctant to announce her success because she was a woman and she feared that the scientific community would not be open to her. William, however, was determined that Maria’s discovery be recognized, and wrote to other influential astronomers in an effort to gather support. He first wrote to his friend and colleague William C. Bond, the director of the Observatory at Harvard College (now University) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The President of Harvard, Edward Everett, then wrote to William Mitchell, asking whether he was aware that Maria could claim a medal from the King of Denmark for her new comet. An amateur astronomer himself, Frederick VI, the King of Denmark, decided to offer a gold medal to the first observer to see any new telescopic comet. Frederick VI died in 1839, but his successor, Christian VIII, continued to award these medals. Maria was almost denied her medal because William Bond and her father failed to follow the proper procedure for alerting the Danish government of Maria’s discovery. However, more than a year later, the gold medal finally arrived on Nantucket. The discovery of the comet, called Comet 1847-VI and informally as “Miss Mitchell’s Comet,” was the event that made Maria famous. She was elected a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, in 1848 as a result. Maria’s father William Mitchell was already a member. Maria was the first female member. Although she was now a famous astronomer, Maria remained librarian of the Atheneum. She was hired by the U.S. Nautical Almanac to track Venus, which, although it is a planet, was used as a navigational “star” by sailors at sea. Maria’s days now often included visits from people who wanted to meet one of the first women to have discovered a comet. Maria sometimes found her fame irritating, since it got in the way of her work. She often found people’s responses to her new social position funny. In 1854, Maria wrote: “My visitors…have been of the average sort. Four women have been delighted to make my acquaintance–three men have thought themselves in the presence of a superior being…One woman has opened a correspondence with me and several have told me that they knew friends of mine….I have become hardened to all.”

- Travels in 1857

Maria had always dreamed of one day visiting Europe, and had carefully saved her small wages for many years in order to be able to afford to do so. In 1857, a banker from the western United States hired her to chaperone his daughter on a trip through the American South and Europe. Maria visited St. Louis, New Orleans, parts of Alabama, and Charleston.

After returning to Massachusetts for a brief period, she set off across the Atlantic to the English port of Liverpool. Once there, she visited the city’s observatory and sent a letter to the author Nathaniel Hawthorne, who was also staying in Liverpool. Maria visited with him, and later contacted him while they were both in Paris to ask whether she could join he and his family. They would later all travel to Rome and to a few other cities in Italy. Maria saw the sights in London, including Westminster Abbey, where she was especially impressed by Sir Issac Newton’s tomb, and the British Museum, where she saw the oldest printed Bible in the world and a manuscript hand-written by Queen Elizabeth I. Later, she went to Cambridge to see the observatory. There, she visited with astronomers including Sir George Airy, the Astronomer Royal, who had established a new Prime Meridian in Greenwich, England in 1851.

One of the highlights of Maria’s time in England was her stay at Collingwood, the estate of Sir John Herschel, one of the most famous astronomers of his time. Sir John’s father Sir William Herschel had discovered the planet Uranus in 1781; Sir John himself later named seven moons of Saturn and four moons of Uranus. Sir John’s aunt, Caroline Herschel, was the first woman to discover a comet. Maria traveled on to Edinburgh and Glasgow before continuing to mainland Europe, including Paris and Rome. In Paris, she saw an observatory that was founded by the French Academy of Sciences during the reign of Louis XIV.

- Travels in Rome

Maria’s next destination, Rome, seems to have been by far her favorite. She wrote the lines noted above on January 24, 1858. Maria spent every minute of her days absorbing the many centuries of Roman history, taking expeditions to sites like the Roman Forum and the Coliseum.

Of course, Maria very much wanted to visit the Vatican Observatory. Having been raised in a Quaker environment on Nantucket, she didn’t realize that she might not be allowed in because she was a woman. Maria was brave enough to ask permission of Father Secchi, the Vatican’s astronomer. Through him, she was able to receive[/modal] approval to visit the observatory, even though Mary Somerville, the most famous woman scientist in Europe at the time, had been denied entry.

Maria wrote that the sky was extremely clear near Rome, and that Father Secchi was working on developing methods of photographing celestial bodies. Secchi is known today for having discovered solar spicules (jets of solar materials) naming the dry channels on Mars as “canali,” or canals, and discovering three comets, one of which is named after him. Maria returned to Nantucket in the summer of 1858, and then moved with her father to Lynn, Massachusetts after her mother’s death in 1861. She continued her work for the Coast Survey and Nautical Almanac until she accepted a post as professor of astronomy at Vassar College in 1865.

- Vassar College – The Early Years

In 1861, when Matthew Vassar founded Vassar College, there were few opportunities for women to continue their education past their teenaged years. Before Vassar, no schools had been specifically founded as colleges for women. The most famous site of higher education for women was Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, which was founded twenty-four years earlier and provided one of the most advanced and complete female academic educations of its time. Because women were not allowed to attend universities or colleges alongside men, schools needed to be created especially for, and only for, women.

Matthew Vassar was clearly impressed with Maria’s success as a scientist, and saw her as a role model for intelligent and ambitious women. She was the first professor hired to teach at Vassar College when it officially opened in 1865. She lived at the observatory with her father.

Maria soon found that her role there was not only as a professor, but also as a mentor and guide for the young women. Maria was expected to act not only as a teacher, but also, in some respects, as a guardian and a motherly figure. Before leaving their daughters at their new school, the mothers begged Maria and the other teachers to take special care of each one and to make certain that they did as they had been told. One urged Maria to make sure that the “lady principal,” Miss Lyman, insist that her daughter curl her hair, since, “‘she looks very graceful with her hair curled.’” Maria couldn’t help but laugh at the fact that she was supposed to be in charge of her students’ development as “proper” young ladies.

Within the first few years, Vassar students had many opportunities to conduct research and observation. Maria took her students on study trips to observe solar eclipses, with the first trip taking place in August 1869 to Burlington, Iowa. Some time later, in 1878, she took students to Denver, Colorado to see a second total eclipse of the Sun. She was known for keeping students up at night past their curfew so that they could observe with her, and she enjoyed a close relationship with many of her astronomy students. She had a reputation for expecting much of her students, but she was a favorite professor of many. She treated her students as equals; she famously said, to her classes, that, “We are women studying together.”

- Her Vassar Girls

Maria’s influence on her students’ development while at Vassar was so great that one of her students would later name her only daughter after Miss Mitchell. Lizzie Champney, who attended Vassar College as Elizabeth Williams, gained fame as an author of books for young girls. She was most known for her series of books that featured the adventures of three Vassar students who traveled around the world, just as Maria had. These books were illustrated by her husband, the artist J. Wells Champney. Maria Mitchell Champney, named in honor of Elizabeth’s favorite professor, was born in 1877. At some point during Maria Champney’s childhood, her parents convinced Maria Mitchell to sit for a portrait so that her namesake could have an image of her. Since she was usually reluctant to sit for portraits, Maria must have been very honored that the Champneys had chosen to recognize her in this way.

Although she had less time to conduct her own research, and she eventually gave up her job for the Nautical Almanac, Maria found satisfaction in teaching students what she knew. She found the same joys at Vassar as she had when she was a young girl in the house on Vestal Street, observing with her father. Maria herself summed up this experience in her own words on March 16, 1885:

“In February, 1831, I counted seconds for father, who observed the annual eclipse at Nantucket. I was twelve and a half years old. In 1885, fifty-four years later, I counted seconds for a class of students at Vassar; it was the same eclipse, but the sun was only about half-covered. Both days were perfectly clear and cold.”

- Return to Europe

Maria made a second trip to Europe in 1873. Russia was another adventure for Maria, since she was traveling outside of Western Europe for the first time. She experienced strange differences in environment like the “twenty hour St. Petersburg summer day.” Still, she also found familiar features amongst the landscape. Some of the Russian villages through which she traveled were made of wood houses, which Maria thought resembled New England villages much more than the “stone and brick villages of England” did.

Maria had decided to travel to St. Petersburg in particular to visit with Otto von Struve, the director of the Russian observatory in Pulkovo, just outside of St. Petersburg. She was surprised to find that von Struve’s wife was very well-educated, and wrote about the fact that the couple told her there were “thousands” of women who studied science at St. Petersburg’s universities. By 1873, Vassar had only graduated two classes, and women in science were still very rare in the United States. “One wonders,” Maria wrote in her journal, “in a country so rich as ours, that so few men and women gratify their tastes by founding scholarships and aids for the tuition of girls–it must be such a pleasant way of spending money.” Maria was impressed with the curiosity and intelligence of the Russian girls she met, who were concerned with politics, literature, and education. They, in turn, admired the “American girl,” who they saw as full of energy and ambition. To this, Maria replied, “When the American girl carries her energy into great questions of humanity, into the practical problems of life; when she takes home to her heart the interests of education, of government, and of religion, what may we not hope for our country!”

Maria also made a brief visit to London in 1873, where she visited the Glasgow College for Girls and spoke to the superintendant. Maria was disappointed in what she heard: this school taught only music, dancing, drawing, and needlework. Worst of all, the superintendant thought that Latin and mathematics for girls was “bosh.” Not surprisingly, in the same year, 1873, Maria helped to found the American Association for the Advancement of Women.

- Retirement and a Return to Lynn

Maria fell ill in 1888. Although she had wished to remain as a professor at Vassar College until she was seventy years old, she left to recover at her sister’s house in Lynn, Massachusetts, just six months shy of her birthday. Faculty and students tried to convince her that she should stay at Vassar, whether or not she was well enough to continue teaching. One letter, dated January 10, 1888, begs, “You will consent, you must consent, to having your home here, and letting the work go. It is not astronomy that is wanted and needed, it is Maria Mitchell.” One of Maria’s nephews, an architect, built her an observatory in Lynn in hopes that she might recover enough to return to observing. Well-loved by her families at Vassar and those with whom she had spent her childhood on Nantucket, Maria Mitchell died on June 28, 1889. She is buried on Nantucket, in Prospect Hill Cemetery, next to her mother Lydia and close to her father, William.

- Legacy and the Maria Mitchell Association

The founders of the Maria Mitchell Association, Maria’s friends, family, and former pupils, formed the organization in 1902 to commemorate Maria’s life and interest in astronomy and the natural sciences. When Maria’s aunt, Mary Mitchell, who had lived in the house at 1 Vestal Street, died in that same year, the Association bought the house at 1 Vestal Street and filled it with displays related not only to Maria’s life, but also to her passions. It was not at first arranged as the house would have been during Maria’s lifetime. Instead, the front parlor was a reading room, and the family’s sitting room was hung with photographs of the Mitchells and also held Maria’s scientific books and instruments. What had been the downstairs bedroom and birthroom was converted into a room for displaying plant, animal, and geological specimens.

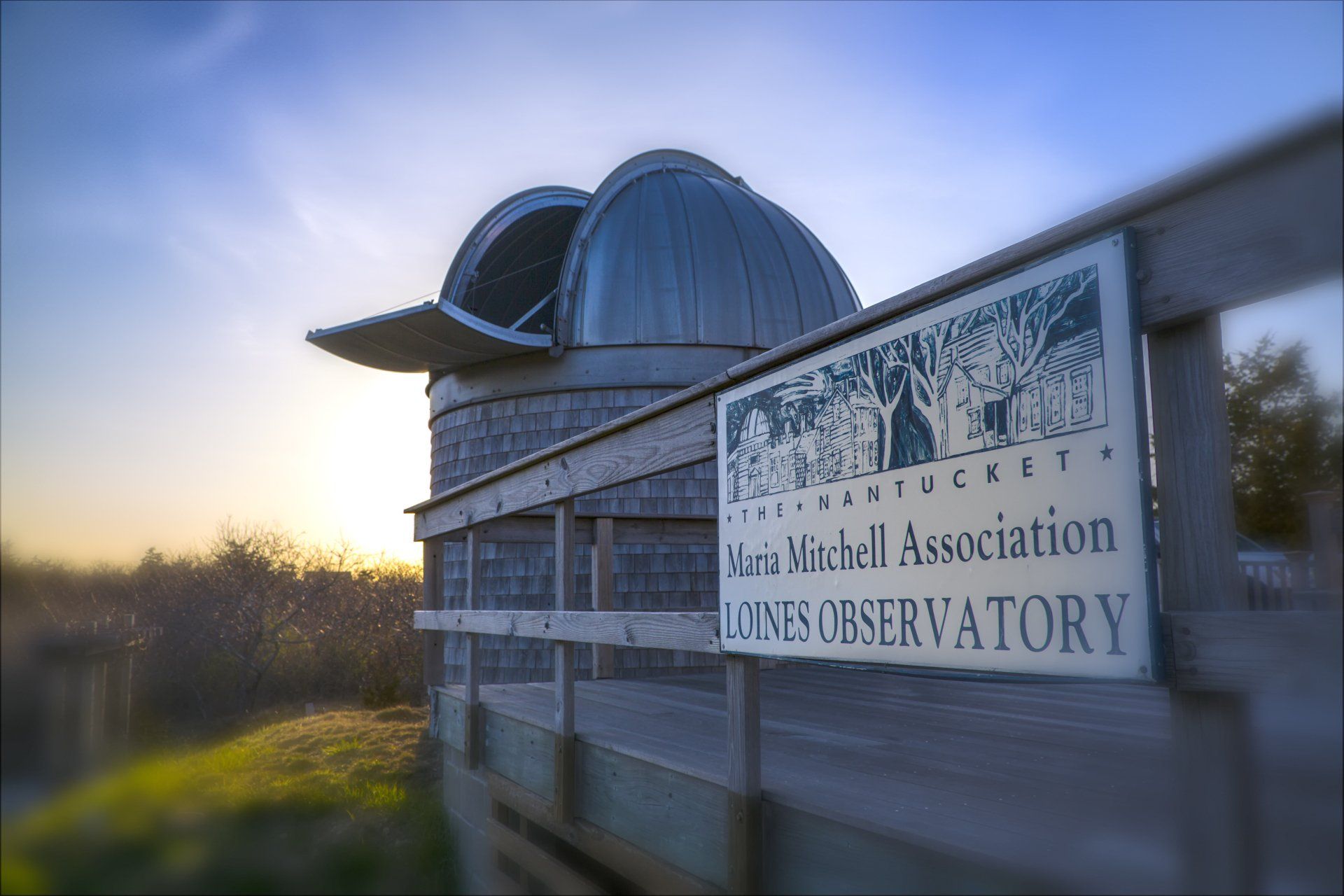

In 1908, the Maria Mitchell Association completed an observatory that still stands next door to Maria’s birthplace where public lectures in astronomy are offered. It houses the 5-inch Alvan Clark telescope that was given as a gift to Maria by the Women of America, headed by Elizabeth Peabody, in 1859. By the 1920s, the Association also offered classes in natural science for adults and children, continuing Maria’s legacy of “learning by doing.”

Today, the Maria Mitchell birthplace is dedicated solely to interpreting the life of Maria Mitchell and her family, and to introducing each new generation to the incredible history of this pioneering woman scientist. The Maria Mitchell Association’s Vestal Street campus also includes Hinchman House, which now houses the natural science museum, and a science library open for research by appointment. The Loines Observatory on Milk Street, with domes built in 1968 and 1998, features a 24-inch research telescope and an 8-inch Clark telescope, the later of which is used to show celestial objects to the public at Open Nights. In 1988, the present Aquarium building on Washington Street, originally a ticket office for the Nantucket Railroad, opened to the public. The Maria Mitchell Association is dedicated not only to preserving Maria’s personal legacy, but also to educating all its visitors about the flora and fauna of Nantucket Island and the wonders of the skies which Maria dedicated so much of her life to observing. Maria Mitchell Association staff and visitors alike bring Maria’s words to life:

“We have a hunger of the mind which asks for knowledge of all around us, and the more we gain, the more is our desire; the more we see, the more we are capable of seeing.” Learn more about today’s Maria Mitchell Association.

- Selected Further Reading

For Children:

Barrett, Hayley. What Miss Mitchell Saw. New York: Beach Lane Books, 2019.

Hopkinson, Deborah. Maria’s Comet. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1999.

For Young Adults:

Anderson, Dale. Maria Mitchell: Astronomer. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 2003.

Gormley, Beatrice. Maria Mitchell: The Soul of An Astronomer. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1995.

For Teenagers and Adults:

Albers, Henry. Maria Mitchell: A Life in Journals and Letters. Clinton Corners, New York: College Avenue Press, ed. 2001.

Booker, Margaret Moore. Among the Stars: The Life of Maria Mitchell. Nantucket: Mill Hill Press, 2007.

Daniels, Elizabeth et al. Vassar Encyclopedia, Vassar College. http://vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu

Hanaford, Phebe A. Daughters of America; Or, Women Of The Century. Augusta, Maine: True and Company, 1883.

Kendall, Phebe Mitchell. Maria Mitchell: Life, Letters, and Journals. Boston: Lee and Shepard Publishers, ed. 1896.

Leach, Robert and Peter Gow. Quaker Nantucket: The Religious Community Behind The Whaling Empire. Nantucket: Mill Hill Press, 1997.

Philbrick, Nathaniel. In The Heart Of The Sea: The Tragedy of The Whaleship Essex. New York: Viking, 2000.

Philbrick, Nathaniel. Away Off Shore: Nantucket Island And Its People 1602 – 1890. Nantucket: Mill Hill Press, 1994.

Wright, Helen. Sweeper In The Sky: The Life of Maria Mitchell. Nantucket: The Nantucket Maria Mitchell Association, 1949.